Trump’s acquittal: American apartheid and the struggle to end it

The United States has more in common than you might think with the overtly racist polity of pre-1994 South Africa - both were founded as settler democracies

“This is not taking place in the Congo. It has nothing to do with Johannesburg or Cape Town. It is not Nyasaland or Nigeria. This is Florida. These are citizens of the United States…”

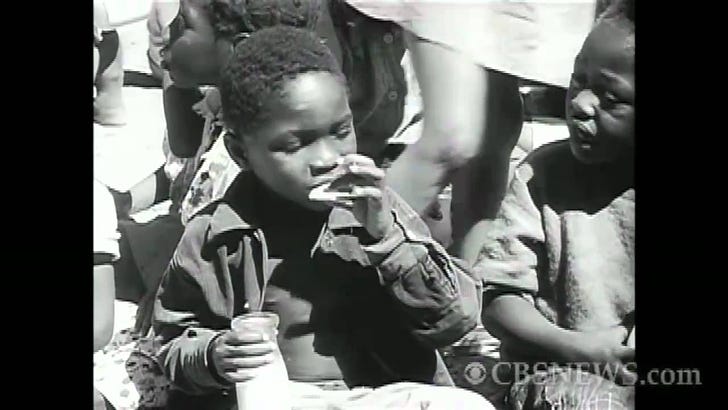

Edward R. Murrow saw it, many, many years before I did, in Harvest of Shame, his blistering 1960 CBS documentary aired on Thanksgiving Day to draw attention to the oppression and exploitation of the Black and brown farmworkers who harvested America’s food.

It was not an idle comparison; Murrow had reported from South Africa in the brutal early years of apartheid, in a two-part documentary series in 1954. And he had covered the civil rights struggles of the United States in the 1950s. He could see how easily the images of desperately poor Black farm workers lining up for day labor in rural Florida he used in the opening scenes of “Harvest” could be mistaken for their peers still suffering in squalor under the colonial yoke in Africa. That, really, was his point.

The connection he was drawing to the circumstances of Black life in the American South in 1960 and under the white-supremacist apartheid regime in South Africa is more relevant, today, than ever — it may even hold the key to understanding the political dynamic underway in 2021 in Washington DC and across the United States of what we should think of as Apartheid America. Not simply as a rhetorical cudgel in the facile way that “fascism” is often tossed around these days, but as a conceptual road map for thinking about democracy and power in the USA.

Of course, we knew that Donald Trump’s second impeachment wouldn’t end in a conviction, because nobody serious imagines that the Senate is really a deliberative body weighing arguments in good faith. Those who have been paying attention are well aware that most of the Republican Party on Capitol Hill comprise the parliamentary wing of the white-nationalist movement that attacked the legislature on January 6. Still, what struck me was the narrative deployed by Trump’s lawyers and his supporters in the Senate to reassure their public of the justness of their cause: Everything Trump and his supporters may have done, they told us, should be read against the events of the previous summer, which they described as a fearsome and deadly offensive (cheered on by Democratic Party politicians) on the lives and livelihoods of white Americans and the noble police departments that protect them — a deadly threat from which they were saved only by Trump’s willingness to order the use of force. As bizarre as this characterization the Black Lives Matter rebellion may be, it certainly sounded familiar to someone raised “white” in apartheid South Africa.

When the Black youth of Soweto rose up in rebellion in 1976, choosing to die on their feet rather than live on their knees, being shot down in the streets when they tried to peacefully protest the racist system that brutally oppressed and exploited them, those of us deemed “white” were told similar lies by those in power. Not that these brave young kids were putting their lives on the line to resist a monstrous evil perpetrated every day in our name, but that they were coming to kill us in our beds, take away “our country” and destroy all we hold dear. And so, as Black townships burned, were summoned to guard duty all night, patrolling the perimeter of our school’s grassy sports fields (facilities unimaginable at any Black school) on the lookout for Black kids we were told would come to burn down our school — some of us wished they would! This attempt to cast us all as little Kyle Rittenhouses was part of preparing us for conscription into the apartheid military (don’t worry, I didn’t buy it; I became a draft-resistor and an anti-apartheid activist, but more on that another time)… Casting heroic protest and rebellion against a system that offered Black people only despair, degradation and an early death as a demonic assault on the wellbeing of white folks was a mainstay of the apartheid regime’s efforts to rally white people to its defense. The same, of course, had been true in the United States in the period of Jim Crow and lynching — reading Robin D.G. Kelley’s compelling history of the Communist Party in Alabama, I’m struck by how the main tool used to rally white support for state and Klan violence against the reds and their organizations was that they were campaigning against lynching and for racial equality, human rights and dignity for Black folks — which the racist local authorities portrayed as a mortal threat to white America.

Trump’s lawyers, and his party, sang the same tune: Trump and his supporters are the defenders of whiteness, from a mythical mob come to destroy it. But to think of the GOP only as a personality cult in thrall to the mesmeric charisma of a TV- and social media personality is to miss the point: Trump is not aberration; his presidency was a Republican triumph, building a genuine mass movement behind the white nationalist-billionaire alliance that has shaped the party over the past three decades.

The GOP has known since long before Trump that America’s demographic trends weigh against that alliance, which is why using the considerable legal means available to it in an already rigged political system to stop Black and Latino citizens voting — and when they do vote, diluting the power of that vote via racist redistricting and gerrymandering — has long been a central strategy of state-level Republican operations.

Trump simply ramped it up, said the quiet part out loud. And he needed to.

Image from this National Catholic Reporter story

Trump’s reelection was prevented by a large turnout of Black, Latino and Indigenous voters in Georgia, Pennsylvania, Wisconsin and Arizona — the fruits of years of patient grassroots organizing by progressives, overcoming sustained Republican voter-suppression efforts. But Trump had prepared his base for that possibility by preemptively delegitimizing those votes. The only way he could lose, he told Republicans, was if the election was rigged. As the results rolled in, he amplified those claims — constructing the Big Lie that drove the January 6 assault on the Capitol. It’s critically important that we recognize that the Big Lie was not simply a narcissistic bully refusing to accept that he’d lost; it was a white supremacist fable, targeting those very centers where BIPOC votes had made the difference. Trump weaponized his party’s unspoken belief that the votes of working-class Black people were somehow not legitimate, that they should not count, that accepting an electoral verdict determined by a Black electorate meant accepting a “steal” that would mean, as he told them, that Trump’s white nationalist base would “no longer have a country”.

(As Brian Lehrer noted in a radio broadcast I heard earlier today, even though Trump lost a significant number of white suburban districts that he’d won in 2016, those didn’t feature in his claims of election irregularities — the “steal” allegations were targeted in line with the white-supremacist narrative…)

Clearly, the subtle-not-subtle messaging that concocted the Big Lie resonates with a large proportion of the tens of millions of white voters who back Trump and what he represents. Those who stormed the Capitol believed the lie, absence of evidence notwithstanding, because they needed it to be true. They needed to believe that white supremacy was the norm, and that democracy would cost them “their” country, i.e. the one in which they literally and figuratively hold the whip hand. Last week, it was reported that 40% of Republicans surveyed by the conservative American Enterprise Institute were willing to accept political violence as a means of securing what they see as their realm.

Just as we were told in apartheid South Africa that Black kids refusing to be enslaved, degraded and murdered posed a clear and present danger to our physical survival, so does the Republican narrative of 2020 cast Black Americans struggling for dignity, humanity and their very physical survival in the face of systematic racist police killings — and, of course, also their political empowerment at the voting booth — as a direct threat to white folks’ wellbeing.

So, expecting the Brooks Brothers arm of white nationalism in the Senate to disavow their movement’s armed insurgent wing was to misread the political stakes.

The U.S. has never been the democracy advertised in its foreign policy. In fact, Republicans have over the past year taken to making clear that democracy was not the intention of the framers of the 18th century Constitution. The USA, they bluntly insist, is not a democracy; it’s a constitutional republic. And we know that constitution, written by and for rich white men, was designed to prevent democracy. What’s changed is that the Republican Party under Trump lost some of its shyness about expressing the white-supremacist tropes that have guided its political program on the ground for decades.

Trump warned us that he could stand in the middle of Fifth Avenue, shoot someone dead, and not lose popularity: The Senate’s verdict on his impeachment trial for ordering a white supremacist mob to storm the Capitol proved he was right — not because of his personal charisma, but because of what he represented to the white American id, and to the political party that expresses it.

The trial’s outcome was predictable precisely because the Republican Party is not out to defend democracy, nor has it been for decades. It adopts an almost Leninist view of institutions, using them when they can advance its agenda and trashing them when it can’t. Any idea that the Republican Party is there to defend the political system rather than its narrow interests would have ended with the fall of the Berlin Wall. The GOP’s purpose is to take and hold power, meaning democracy is actually a threat. That’s why even those Georgia Republicans who refused to buckle to Trump’s pressure to act outside the law have nonetheless for years acted within the law (which provides them considerable leeway) to prevent working-class Black citizens from getting to vote. Even now, those same state-level Georgia Republican Party functionaries that bucked Trump are trying to use the law to suppress the work of the organization that mobilized the Black vote in Georgia. Somebody needs to explain to Nancy Pelosi that the Republican Party is not a partner in democracy; it’s an obstacle to democracy.

Thus the willingness of so much of the GOP to indulge and believe the Big Lie. And it would be extremely dangerous to ignore why tens of millions of mostly white voters were ready to believe that Black votes were illegitimate — and why many thousands of them are willing to take up arms against fellow Americans in support of it. The steal is a lie that “white” America — those that identify with and demand white supremacy and privilege — actually want and need to believe. When they talk about “our country” they don’t mean the diverse America of today; they mean a system of white power and privilege. In South Africa, we called it apartheid, the essence of the system being not so much the segregation implied by the word (Afrikaans for “separateness”) as much as its underlying system of white rule and Black subjugation. The checks on democracy built into the US Constitution give the GOP plenty of legal machinery to protect American Apartheid. But history has also shown that sometimes, a bit of white terror is required to achieve the same goals. America saw that during the Reconstruction era after the Civil War, when the brutal extra-legal violence of the lynch mobs was deployed to prevent Black people from exercising their newly codified Constitutional rights. January 6 may be a sign that we’ll be seeing another season of white terror aimed at rolling back the small-d democratic threat to white supremacy.

American apartheid. Now there’s a thought.

BTW, a quick note on terminology: I use whiteness to refer to an ideology, not to a fixed group of people with inherited physical traits. Whiteness is a social and political identity constructed in support of and privileged by a system of domination and subordination of those deemed ‘other’. But Apartheid is a concept that needs some explaining, also, because it’s so important to making sense of the mess we’re in right now, the nature of the escalating political turbulence through which we’ve lived for the past two decades, and perhaps even to help us think our way onto a path to democratic equality in the United States.

By considering the US political system through the apartheid lens, we can more accurately plot the current location of the U.S. on a journey towards democratic equality, and the road ahead. (Spoiler alert: It’s a long road…)

The phenomenon described by apartheid existed before the term did — nor does the word’s literal meaning convey the common origin story and shared political DNA between the political systems in the old South Africa, today’s Israel, and the United States. Apartheid is about a lot more than segregation; nor is formal segregation necessarily always a feature of states of this type. Indeed, we might more accurately refer to these states as settler democracies.

The defining feature of these systems — notwithstanding their distinct histories, conditions and characteristics, the forms of resistance they encountered, their resultant evolution along different trajectories — is that they are at once democratic (governments chosen in competitive elections, the rule of law etc.) and structurally racist. That’s because all were nation-states created by settlers who sought to break free of their colonial sponsors by creating states of democratic self-governance, while at the same time restricting that democracy on "racial" lines to avoid it empowering the Black/Brown/Indigenous people living within those states, whose displacement, subordination and/or exploitation were key to the ambitions of the settler population.

That origin story is shared by the US, South Africa and Israel. A failed shorter version was attempted over two decades in the former British colony of Rhodesia, before it became Zimbabwe. It’s also true for Canada, where First Nations were only given voting rights a century after democratic self-government began; in Australia where what was left of the indigenous population after the ravages of white settlement were only given voting rights six decades after democratic self-government began; New Zealand (reliably) had a more liberal history, though far from unproblematic.

(I’d love readers of this newsletter with any thoughts on the above, or knowledge of equivalent processes in Latin America to share examples if there are any, i.e. democracies established for settler populations that excluded Black and/or indigenous people.)

We’re not going to go into the history, here, of how mass struggles forced the settler polity to open democratic rights to Black people, then to painfully shut them down, prompting further struggles — and the reality that we’re living through a moment where the central strategy of the party of apartheid (white minority rule) is to roll back the gains of the 1965 Voting Rights Act and the Civil Rights era, lest democracy endanger Republican rule.

All of the Republicans’ apartheid work at state level to deny BIPOC voters access to the polls failed to stop the election being won by Biden, precisely because of the anti-apartheid work done at the grassroots to organize a massive turnout of those voters. Fear of a Black electorate is exactly why Trump and his party seeded the ground for the Big Lie they rolled out on Election Night, targeted at the BIPOC turnout had flipped states for Biden. The Republicans were essentially telling their white base what they wanted to hear: That the votes of Black and Latino voters were illegitimate, fraudulent — part of a devious plot to rob them of “their” country, meaning their privileged status in a settler democracy.

Fear of a Black electorate — and of democracy — remains a core theme of the party of American apartheid, just as it was for the white minority regime under which I grew up in South Africa.

Trump lawyer Michael Van der Veen’s closing arguments in the Senate trial — stirring the fears of Republican voters about a risen Black population challenging the murderous systemic racism in US policing reminded me of what I heard as a teenager in white South Africa during the 1976 Soweto uprising: The police had to kill Black people to “keep them in their place”, or else they’d come and kill us.

Today’s political drama in the US is not a case of a "democracy" suffering an authoritarian hiccup; it's a settler-colonial system that has been slowly and unevenly democratized through bitter struggles by the excluded over almost two centuries, and which is now suffering a white-nationalist backlash to much of the progress that has been made towards establishing a genuine democracy in America.

To respond effectively, though, we must begin by recognizing that American democracy is an unfinished project; the institutions and practices of settler democracy bequeathed by the constitution were not designed to create a society where everyone, and every vote, has equal value. But while those institutions can be effectively used to block progress towards democracy, they can and have been effectively used, also, as vehicles to pursue democratic equality — when driven by grassroots organizing and struggle outside of the corridors of power.

The GOP is seeking to limit the extent to which the constitutional system can be used to democratize America. So, we are challenge to both defend democratic gains that have been made over centuries of struggle — remember, the Founding Fathers never intended that Black, Indigenous and Latino Americans would vote (or would even be recognized as citizens); they never even intended white women or white men who owned no property to vote — and at the same time never lose sight of the goal of extending them. The United States of America will never be a true democracy until every citizen is able to cast a vote of equal value in choosing our government. And we were a long way from that goal before Trump and his Capitol riot. Then again, the white nationalist backlash that is Trumpism and today’s Republican Party may be a sign that in the big picture, we’re making progress, after all.

Pre-Trump “normalcy” wasn’t even close to a society of democratic equality. There’s a long way to go. Lots more thoughts to follow, in this newsletter, on lessons we can learn in America from other anti-apartheid liberation struggles (like the importance of Black working-class leadership in the democratic struggle!). And please share your thoughts!