Palestine, College ‘Marxism’ and the Morbid Dialectics of Social Media

Why you'll have to put down your phone to defeat fascism. Also, what to make of David Brooks channeling Georgi Dimitrov...

Donald Trump’s war on radical thought in U.S. college curriculum is part a longstanding campaign of populist demagoguery among Republicans designed to delight the MAGA base, for which the Trump Administration’s economic policies are unlikely to deliver: You’re going to be paying more for most of what you need, the public services on which you rely are going to shrink and disappear, and your job could be ended by a recession — but hey, we’re sticking it to those smug Ivy League elitists who look down on you as a “basket of deplorables”. It’s another classic Trumpian Wrestlemania performance.

Trump’s movement uses the term “Marxism” in a manner devoid of any connection to analytical concepts Karl Marx might recognize, much less any connection with organized political struggle to bring down capitalism and imperialism mandated by his corpus of ideas.

Like “woke”, it’s a capacious descriptor used to deride all language and practices that challenge the right of rich, white men to rule the world. Its current target is the DEI policies adopted in the neoliberal era by universities, corporations and other public institutions to diversify the elite tiers of the stratified and profoundly unequal capitalist class structure. The neoliberal identity politics often derided as “woke” accepts, or at least assumes the durability of capitalist inequalities; it simply seeks to ensure there are more people of color and diverse gender and sexual identities in the boardrooms. Quite the opposite of Marxism, really.

But the MAGA war on liberal arts radicalism got me thinking about how American leftwing thought was defanged by its retreat into university settings to escape the McCarthy witch hunts. American Marxism, once grounded in working-class and popular mass struggle, has been transformed into an esoteric academic pursuit, whose political dimension such as there were any became increasingly fixated on language, identity and representation. And also, about how those trends shaped the backlit militant poetics, quite harmless to lived power relations, that later came to predominate in social-media radicalism.

Despite its power to highlight injustice, social media functions more as a means of pacification than as a vehicle for mass collective action

In the case of Palestine solidarity, the norms of smart-phone agitation and social media’s fetishized political combat can sometimes dull the political senses. A liberation struggle is not a debate; it can’t be won in a seminar room or in a twitter fight. Nor is it reducible to a contest over identity and representation, visibility and erasure. A violent settler-colonial entity won’t be shamed into surrender. So, despite their tremendous, proven potential to highlight injustice and popularize disgust against it, social media platforms arguably function more as a means of pacification than as a vehicle for mass collective action: The atomized individual engages, alone, passive except for their thumbs, on an imaginary town square conjured in their smart phone. They pour their rage into what feels like fierce political combat – but it’s a “battle” inside a digital simulacrum that offers a simulation of struggle not too dissimilar from first-person shooter video gaming.

There’s no question of the power of social media to show those individuals the brutal reality mostly elided by corporate media – the Palestinians of Gaza would be murdered in the dark if not for social media’s real-time ability to bypass mainstream media’s pious obedience to Zionist gatekeepers. But as long as their reaction is confined to social media, they remain harmless to the genocidal project. It’s only when they put down their phones and gather, in person, for organized collective action to disrupt the genocide, that they present an effective challenge.

Zionism can’t be canceled; the struggle to free Palestine, like all liberation projects, is fundamentally a struggle over power. Success requires strategy: A systematically conceived set of collective actions across a wide range of terrains designed to building the power of the oppressed to resist, disrupt, weaken and eventually break the shackles of settler colonialism. That strategy necessarily includes a thoughtful, continuous program of eroding, dividing and disorganizing the consensus of power that sustains those shackles. Failing to recognize, assess and respond to consequential shifts in the balance of forces is to choose oblivion.

Yet, social media often elevates and amplifies a brand of radicalism disconnected from (and often oblivious to) any strategy to shift the balance of power in favor of the liberation project. It lends itself to a kind of cost-free “influencer” gatekeeping and posturing empty of any kind of strategy beyond exciting a frenzy of otherwise passive likes, shares and comments.

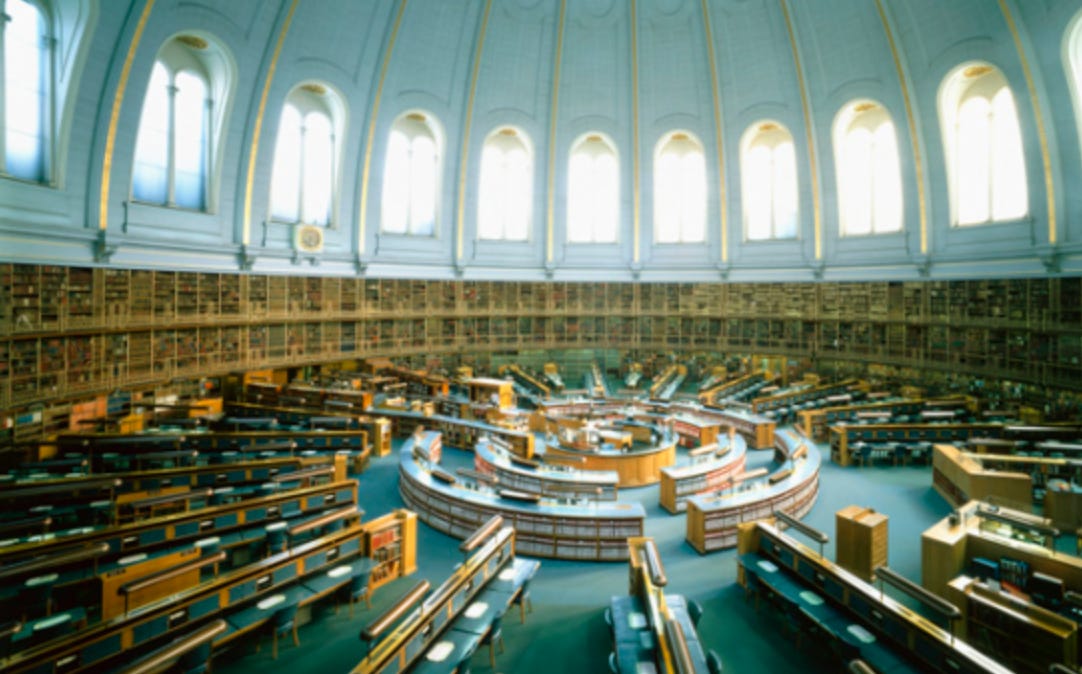

And, with the U.S. now decisively recentering its domestic politics and foreign policy in a post-Post Cold War frame, it’s worth exploring the limits of the forms of leftwing contention adopted during the Cold War (library leftism) and the post-Cold War (influencer insurgencies).

* * *

Leftist theoretical work in the United States pre-World War 2 had been grounded in radical mass movements, trade unions, and political parties waging an existential power struggle with a capitalist system destroying the lives of millions as it lurched, increasingly violently, through decades of profound crisis. The struggle against greedy owners unleashing naked violence on unionizing workers, against racist lynch mobs donning white hoods at night and police uniforms by day to keep Black America down, were struggles of blood and guts, cracked skulls and buried martyrs. It took the social democratic concessions of the New Deal, and then the industrial boom of World War 2 and its aftermath to put American capitalism on a more sustainable social path to survival; it had looked pretty touch-and-go in the 1930s, even in the minds of the ruling class.

So, the epicenter of Marxist study in the first half of the 20th century was not the college library or seminar room; it was in the night schools and reading circles of working-class activists seeking to birth a better world against terrifying odds.

Yes, the party faithful were often fed a narrow and doctrinaire Marxism, more catechism than dialectic, overdetermined by the (retrospectively absurd) belief that October 1917 — an epic historical fluke created by a profoundly anomalous set of conditions unique to Russia at the time, never mind the horrors created by its militarized method of political organization — provided a global revolutionary handbook. Still, the purpose of studying radical thought was never to acquire knowledge for its own sake; knowledge was seen as a weapon for transforming a violently unjust world. Marx’s 11th thesis on Feuerbach was the unstated motto of these imagined universities of an imagined proletariat: “The philosophers have only interpreted the world, in various ways; the point is to change it.”

World War 2 provided a kind of time-out on the epic social struggle to determine which class would rule America. And stabilizing the postwar order required a new elite political consensus, shaped by and grounded in the Cold War — an imperial imaginary in which the U.S. led “the free world” against an existential threat from the Soviet Union in every corner of the planet. It was in this period that America’s national identity was recast around often-hollow proclamations of global freedom and democracy, requiring a domestic social compact designed to neutralize the threat of working-class rebellion and a degree of racial inclusion aimed at forestalling the threat of Black America being drawn into the Soviet camp.

Eliminating domestic challenges to American capitalism and its Cold War imperial project also required a systematic crushing of the organized political left: Hence the McCarthy era, and the hounding of communists and their fellow travelers out of public life, whether in unions, social organizations, politics or cultural production.

The McCarthy with-hunts drove many radical intellectuals to seek sanctuary in the university, an institution dedicated to open inquiry and freedom to explore ideas outside of the mainstream. Where Marxism in America had once been taught in Communist Party night schools to equip working-class cadres with the conceptual tools of revolution, it now became a largely defanged academic pursuit mostly housed in the respectable Liberal Arts disciplines of Sociology and History, deliberately sanitized to survive the enduring legacy of McCarthy by restricting itself to being simply another model of social analysis. Interpreting the world would suffice.

Thus the emergence of a kind of “library left”, almost entirely divorced from any kind of political organizing. It even produced its own celebrities, unconsciously mimicking mainstream popular culture — think Noam Chomsky or Judith Butler or Slavoj Zizek — but none of these were grounded in any organization; they were the leftist “influencers” of a pre-social media era.

American radical thought, once grounded in mass movement-building, on college campuses became focused on literary and cultural criticism, preoccupied by linguistic framings, identity and representation. The seminar room became a kind of fetish theater of revolutionary struggle, language often its priority prize, with each revision of elite-left nomenclature was hailed as a significant victory. As Adam Tooze recently observed, the sociology of America’s campus left can be read as that of a group “pursuing an arcane and niche strategy of cultural power within the professional managerial class,” leveraging its “highly exclusive symbolic capital.”

But if the victories of library leftism made no splash in the sea of indifference beyond the campus perimeter, their reach was explosively expanded by the virtual soapbox of social media. Esoteric disputation over narrative and representation, once the preserve of the tenured academic influencers, was now digitally democratized — now anyone with a smart phone, some time to kill and creative chops, could become a more entertaining mimic of Chomsky, Zizek or Butler on platforms that rewarded a choleric radical posturing but posed no material challenge to power.

Still, Gaza has also shown how social media’s power to disrupt the narratives of Western power have rattled American elites uncomfortable at the prospect of their own children seeing the racist slaughter abetted by their parents — see the concurrence between Mitt Romney and Anthony Blinken on the reasons for Congress moving to ban Tik-Tok.

So, social media has provided an indispensable space in which the youth of the world bears witness and, sometimes, responds offline to the Western-enabled Israeli genocide. But its limits are also clear: 19 months of twitter/Tik Tok/Instagram insurgency have failed to restrain the bloody hand of the genocidaire or change the calculations of his enablers.

We’re in an extremely dangerous moment. Israeli apartheid rampages, unchecked, through Palestinian bodies in Gaza and the West Bank and bullies the wider region, enabled by the longstanding bipartisan U.S. establishment consensus. And, at home, America’s own apartheid forces have unleashed state power in an aggressive campaign to smash dissent.

They won’t be stopped on social media, nor, really, by a politics that conforms to its norms of contestation. Weirdly, it has fallen the likes of the moderate Republican David Brooks, alarmed by the dismantling of the post-WW2 liberal order, to articulate a what sounds like a classic mature-leftist clarion call to anti-fascist mass action.

Brooks is obviously not a person of the left, and he seeks the restoration of a problematic social order that paved the way for where we are now. Still, it’s worth taking note when such establishment voices are calling for “a comprehensive national civic uprising” led by “one coordinated mass movement”, because “Trump is about power” and “the only way he’s going to be stopped is if he’s confronted by some movement that possesses rival power.” And there’s a clear limit to how much power can be built, much less wielded, via social media. Instead, Brooks looks to the history of nonviolent uprisings that combined tools as varied as “lawsuits, mass rallies, strikes, work slowdowns, boycotts and other forms of noncooperation and resistance”.

He cheers the mass mobilization of the Bernie Sanders-AOC rallies against oligarchy, but sees those as too grounded in electoral politics to suffice. He veers almost reckless in his enthusiasms: “Sometimes they used nonviolent means to provoke the regime into taking violent action, which shocks the nation, undercuts the regime’s authority and further strengthens the movement. (Think of the civil rights movement at Selma.) Right now, Trumpism is dividing civil society; if done right, the civic uprising can begin to divide the forces of Trumpism.”

It's easy to mock the belated anti-fascist militancy of a dyed-in-the-wool conservative, and no doubt doing that will be a brief amusement for many Instagram insurgents. But Brooks is hinting at four key truths long established in the canon of 20th century revolutionary writings from experience on the Left:

1) Oppression is about power, and defeating fascist rulers requires mustering the power to disrupt and ultimately overcome their diktat — it requires mass action across a range of fronts.

2) Elections are an insufficient route to mustering the power to defeat fascism in a U.S. system constitutionally designed to negate the power of the majority.

3) As important as building the power of the majority against fascism is dividing the enemy camp, weakening its consensus and isolating the most dangerous elements.

4) An effective anti-fascist movement requires a coordinating center guided by a clear strategy — a strategy grounded in the principle of maximizing united action among forces who hold different, even contending political visions, but who can be united to take action around minimal points of agreement to defend existing democratic space.

The European left began the 1930s believing capitalism was on its last legs, and that what was required to topple it and win the day for socialism was an uncompromising revolutionary program that dismissed even center-left social democrats as a dangerous enemy. “Those who are not with us are against us.” It ended the 1930s brutally chastened by the victories of fascism, and recognizing that the fascist onslaught had called for defensive politics to preserve democratic spaces, by seeking the broadest ‘Popular Front’ that allied the left with all political forces seeking to preserve democracy, i.e. on a minimal consensus to act together for limited demands. “Those who are not against could be with us.”

Those lessons seem eerily relevant to today’s conversations.

Tony!

Good one.

The real self-isolation of the American Left to campuses began with the rise of Reagan and Thatcher.

Radical anti-war, civil rights, radical feminist, queer movements among others were powerful forces that were eviscerated by the self-destruction of trade unions, socialist parties and the anti-democratic deformations of the post-colonial regimes.

At the same time, the rise of Gazza and “give me lots of MONEY” created a crazed individualism that now finds its expression in the self-commodification of identities on social media.

The intellectual consensus for self-commodification was built around post-modernism on campuses.

As capitalism gave itself a dramatic lease of life through among others financialisation, a new and radical technological revolution combined with the rise of a globalised capitalism in China - the Remains of the Left could not develop a social, economic, political and cultural programme that unified all dominated classes.

Left theory and “action” fell between the Scylla and Charybdis of identity politics and the charred ideological remains of socialist movements. Unable to understand the social, political, cultural and economic destruction caused by the neo-liberal revolution, we have to return to basics.

While I agree that keyboard activism is ephemeral and often self-promoting, the left has failed to utilise the potential of the algorithm in the way that fascists and White Supremacists have done.

We must speak about social media and AI.

Love the note and let’s build the broadest and deepest international popular front against fascism and Bonapartism.

Love

Your favourite Teenage Trotskyist.

Z

Thanks Tony, excellent analysis. "Those who are not against could be with us” means being able to work with people and organisations that one don't necessarily agree with in the relentless pursuit of winning over the 'middle ground' to help tip the balance of power, something, as you point out, that the left, historically and today, is pretty bad at doing. I completely agree with your point about how the retreat to social media has effectively blunted mass action. The only point I would add is that part of mass action and alliance building involves being able to successfully challenge dominant narratives and cultural hegemony, and posit alternative visions, so I would view the world of AI, Bots, and social media as a complementary site of struggle.