Making sense of another "shot heard around the world"

What we learn about the prospects for social justice struggles in the U.S. from the fallout from the failed assassination attempt on Donald Trump

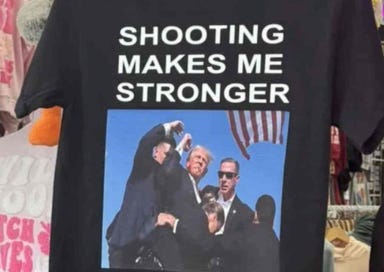

Saturday’s failed assassination attempt on President Trump has certainly increased his chances of beating an increasingly incoherent Democratic Party in the Electoral College that chooses the U.S. President in November. Then again, Trump, leading a right-wing nationalist movement with massive corporate billionaire backing (and other unfortunate historical echoes) had looked set for victory in that bizarre electoral system even before a callow youth of indeterminate mindset shot a hole in his ear, creating the enduring image of defiance that most strongman candidates can only dream of.

(Regarding the Electoral College, a reminder: Joe Biden won 7 million more votes than Donald Trump did in 2020, but he is President only because of the 10,000 votes by which he won Arizona’s Electoral College seats, the 11,000 votes that handed him Georgia’s, the 80,000 votes that won him Pennsylvania, and the 20,000 by which he won Wisconsin. If those 120,000 voters had stayed home, Trump would have been reelected president despite finishing 6.88 million votes behind Biden.)

Indeed, if we view the U.S. system not via its own ideological narratives, assumptions and propaganda about itself, but instead from a deeper historical perspective centered on its global role, the Trump shooting highlights number of key features worth noting — and portends an acceleration of more perilous times amid the long-term collapse of the U.S. governance consensus built after World War 2 to fight the Cold War.

“Political Violence Has No Place in Our System” and other myths

The proclamations by so many establishment politicians in the wake of the shooting that violence is somehow alien to the U.S. doesn’t survive the scrutiny of any given week’s headlines, much less a cursory glance at U.S. political history. And then there’s what the rest of the world has seen and experienced; those parts of U.S. history that happened overseas, and which once prompted Martin Luther King, Jr. to denounce the U.S. government as the “greatest purveyor of violence in the world today.”

The Trump rally attack was just one of 17 mass shootings across the United States last week – a pretty average toll, actually. There had been 261 mass shootings in the U.S. in the first half of 2024. The military style rifle used in the attack was legally purchased; there are literally more privately-owned guns than people in the United States, and firearms are the leading cause of death for American children and teenagers.

The Trump shooting occurred on a day when bombs supplied by Joe Biden were used by Israel to kill 100 Palestinians in a tent camp in Gaza, just the latest victims of a U.S.-enabled genocide that has killed up to 180,000 Palestinians according to the British medical journal Lancet.

Nor is an attempt on the life of a political leader an aberration in U.S. history: Four presidents have been assassinated while in office (Lincoln, Garfield, McKinley and Kennedy), while Reagan, Ford, and FDR survived attempts. Presidential candidate Bobby Kennedy wasn’t as lucky in 1968, nor was George Wallace in ’72 (who was maimed). And, of course, MLK, Malcolm X, Fred Hampton, Medgar Evers and so many more remind us of the pattern of assassinations of Black liberation activists. The American national story, celebrated on July 4, begins with a mythologized “shot heard around the world” that started the settler-colonizer community’s war of independence from Britain. And the country was literally built on genocidal violence against indigenous people and the brutalization of enslaved Africans.

That violence has long extended beyond these borders: the ghosts of millions of dead Filipinos, Vietnamese, Iraqis and many others might laugh bitterly at Joe Biden’s insistence that violence is “not who we are”. Hundreds of Black Americans murdered on their own streets by men in uniforms bearing the U.S. flag might join them.

As political prisoner Jamil Al Almin (formerly H. Rap Brown) once said, “Violence is as American as apple pie.”

Civil war?

The “polarization” decried by so many establishment voices since Trump’s shooting should also be read in historical perspective. And, of course, with a grownup sense that political polarization is actually quite natural in a society as historically and contemporarily violent, and as profoundly unequal as the U.S. The current political pattern began with the end of the Cold War, and the post WW2 national-security-state consensus in which “partisanship ended at the water’s edge”. The forerunner of Trump’s nationalist GOP was Newt Gingrich’s scorched-earth politics, while the Wall Street-Democratic Party elite busied themselves with a neoliberal remaking of the world economy (albeit with greater diversity in high places) that hollowed out the U.S. industrial base and consigned its labor force to a poverty and misery that drove many to opioids, alcohol, and white-nationalist rage. The “war on terror” momentarily rekindled the dying flame of Cold War-type consensus in Washington, but even that was short-lived.

Trump took charge of the GOP in 2016 as the champion of the historical white supremacy on which America was built, arisen to defend “American greatness” from a mythical mob come to destroy it. But to think of Trump’s GOP only as a personality cult in thrall to the mesmeric charisma of a TV- and social media personality is to miss the point: Trump was the culmination of three decades of work to build a genuine mass movement behind a white nationalist-billionaire alliance to cement its long-term rule.

Already in 2016, it was clear not only that there’s no longer any governing consensus in the U.S. – the Trump presidency, the Republican capture of institutions (particular courts and state legislators) using the less-than-democratic constitutional system, and the violent theatrics of Jan 6 highlighted the extent to which there’s no longer a shared national imaginary undergirding the U.S. system.

As Adam Serwer wrote at the time, the post-Cold War GOP imagines itself to be America’s only legitimate ruling party. The reason his supporters believed the “Big Lie” about a stolen election is an underlying belief that “Biden’s win is a fraud because his voters should not count to begin with, and because the Democratic Party is not a legitimate political institution that should be allowed to wield power even if they did… The Republican base’s fundamental belief… is that Democratic victories do not count, because Democratic voters are not truly American. It’s no accident that the Trump campaign’s claims have focused almost entirely on jurisdictions with high Black populations…Black votes are considered illegitimate even if they are legally cast... Demanding that Black votes be tossed out is not antidemocratic, because they should not have counted in the first place.”

The eschatological militancy of Trump’s white nationalist base, together with the rhetoric of Republican leaders (“some folks need killing” according to the party’s nominee for North Carolina governor) may have created an impression that this slide towards a potentially violent zero-sum politics is exclusive to the political right. But research suggests that even more Americans believe violence is justified to stop another Trump presidency than the number who believe violence is justified to ensure one.

So, we’re witnessing the morbid symptoms of a long-term collapse of the political system’s ability to secure the consent of the governed, or even to maintain a basic domestic political stability around a shared national identity. Biden’s sense of “who we are” and what America stands for is firmly grounded in the Cold War certainties of the last century. Thus his hapless efforts during his presidency to restore the bipartisan spirit that forged compromises in the Senate men’s bathroom of that era. But the Republican party has moved on, unceremoniously dumping it’s old Cold War establishment in the dustbin of history and futile “never-Trump” exercises like the Lincoln Project.

Biden can impress Rachel Maddow with his remixes of the greatest hits of the Reagan back catalogue, but most of the world has little track with the NATO agenda, and both U.S. allies and adversaries have come to recognize the fundamental instability of the post-post-Cold War U.S. Iran makes a historic deal with Obama, only to see it torn up for no reason by Trump. Saturday’s news will have sent a shiver through the corridors of power in Kiev.

A boomerang effect?

The great Caribbean anti-colonial intellectual Aime Cesaire, considering Europe’s response to Nazism, used the concept of a “boomerang effect” to note how the genocidal Western violence against colonized people that had been normalized over centuries was now being unleashed on European populations.

We know the long history of U.S. violence abroad, and how that violence also shaped state violence at home — the impact of imperial counterinsurgency wars in the Philippines and Vietnam on how U.S. cities are policed is but one example. But even in the 21st century, the U.S. has showed its citizenry – and the world – plenty examples of a belief among those in power in Washington that violence is a legitimate way solve problems. The invasion of Afghanistan and Iraq destroyed hundreds of thousands of lives; even without sending troops into battle, President Obama killed as many as 800 civilians via drone strikes; Trump preferred performative assassinations like the killing of Qassem Soleimani. And then, of course, enabling Israel’s genocide, another bipartisan consensus.

Perhaps the elites professing shock at the idea of violence as part of U.S. political identity don’t know their own history because so much of it happened overseas, but it has long been a norm rather than an aberration for U.S. decision makers to order the killing of people it brands as dangerous threats to American wellbeing. So, it’s not hard to see how the boomerang effect can also apply when both the Democrats and Republicans see their domestic adversaries as dangerous threats to their own idea of American wellbeing.

The Democrats’ Dilemma

The drama of the Trump assassination attempt and the threat of even greater instability appears to have silenced the Democratic Party’s mutiny against Biden running again. But the damage to the Democrats is far deeper. The shooting has blown a hole in the narrative centerpiece of the party’s campaign: The Democrats are not campaigning on the basis of any particular vision or policy platform; the overriding, almost exclusive theme of their campaign is simply that Trump must be stopped, that he is a felon and a fascist who poses an existential threat to American democracy, etc. And many Republicans were quick to blame that narrative for creating the climate that inspired Saturday’s assassination attempt.

That’s why the Biden campaign immediately pulled its campaign ads and canceled events following the shooting, as Republican figures blamed the assassin on the Democrats’ demonizing of Trump. You can see how if you’re telling people that Trump is Hitler and his support base is the Confederacy, you are also potentially inviting some Americans to respond in the violent ways their narrative tells them are warranted, necessary and even heroic in response in response to existential threats to the nation.

But if the Democrats are restrained from demonizing Trump and centering their campaign, once again, simply on fear of Trump, they’re left trying to answer the question of what they are beyond “not Trump”. It’s not something the Wall Street Democrats have proven very good at over the past three election cycles, i.e. producing a party that seems to stand for something beyond managerial tweaks and diversifying the coterie who occupy the corner offices of a bleak status quo. And Biden is the incumbent in a status quo that most Americans feel isn’t serving them, never mind the millions appalled by his enabling of the Gaza genocide.

Surviving the assassination attempt now positions Trump (already ahead in the handful of Electoral College states that will decide the election) both as victim/strongman, but also as graceful unifying figure, appealing to middle-class voters fearful of violent turmoil by casting himself as the antidote to chaos, promising to bring the country together and ensure stability -- on his terms, of course, which will dramatically limit the space for dissent. (Trump has, for example, promised to violently suppress Palestine-solidarity protests in the U.S.) Rather than bash Biden now, when the sitting President clings to the ropes in a state of confusion, Trump is suddenly talking about “uniting America”, planning to deliver something more akin to a State of the Union address rather than pugilistic red meat. Is he acting as if he’s already won, making his second term seem inevitable in the eyes of the handful of swing-state voters he has to convince?

Shock Doctrines and Reichstags

Naomi Klein’s “Shock Doctrine” warned us against elite decision makers using moments of crisis — wars or natural disasters — to implement preexisting agendas that citizens would normally reject, but which they can be persuaded to accept when events have put them in a state of fear and panic. We saw it after the attacks of 9/11, which the Bush Administration leveraged with barefaced lies, to gain public and bipartisan acceptance for the invasion of Iraq and the massive expansion of the surveillance state, torture and other repressive measures. And historically literate social media saw plenty of references, after the Trump shooting, to the Reichstag fire: The 1933 event in Berlin that created a climate in which the left was portrayed as a violent threat to order in Germany necessitating the sharp curtailing of civil liberties, freedom of the press and the outlawing of political opposition, all of which intractably consolidated the Nazis’ hold on power.

No two historical situations are identical, but despite their differences they can hold lessons. And there are certainly reasons, based on previous statements and positions, to fear that Saturday’s failed assassination could have a profound, transformative and profoundly negative effect on the domestic political space for dissent in the U.S.

Getting real

Viewing the 2024 election through a global perspective freed of the ideological baggage that shapes most Western media coverage, which accepts at face value the palpably absurd stories the U.S. tells itself about itself. It’s fatally flawed to imagine a U.S. elections as an exercise in which the citizenry decides democratically how and by whom they are to be governed. The U.S. Constitution has created a system that is not the democracy advertised on its packaging; its structural design thwarts democracy — from the Electoral College to the 2-seats-per state Senate which can be owned with less than 20% of the national vote, yet which holds veto over policy and picks the Supreme Court, the fact that politicians get to choose their electorate via redistricting etc, the fact that bribery if effectively legalized through campaign finance laws… I could go on, and probably will at some point.

But those looking to make sense of the U.S. both at home and abroad need to reckon with the reality that many millions of votes are unlikely to matter in a system where a candidate might finish second by 7 million of votes and still be declared the winner. Those following from abroad may be tempted to inquire about what foreign policy positions are being staked out in the campaign, but that reflects a naïve fantasy that there’s any necessary connection between what candidates say on the campaign trail and how they govern once elected. Again, the evidence against that premise is overwhelming.

In 2020, I did a thought-exercise piece imagining if the Carter Center’s criteria for assessing the democratic standards of other countries’ elections were applied to the U.S. itself. It’s pretty obvious, by those criteria, why even the conservative Economist Intelligence Unit characterizes the U.S. as “a flawed democracy”.

The liberal American political order of the Cold War era is dead and buried, and anyone elsewhere in the world imagining the U.S. playing a positive role in resolving the crises facing humanity for the foreseeable future is likely to be disappointed. Those fighting for social justice on these shores are going to be facing a harsh, new reality in which the limits of electoral politics and seeking deliverance from the courts are going to be harshly reiterated. Then again, such progress towards justice as we’ve seen in American history didn’t come from the working of its institutions; it was achieved through social struggles in the face of conditions of violent repression often even harsher than what looms on the immediate horizon. History teaches us that the terms and conditions of those struggles may change, but the drive for justice among those denied it can’t ultimately be suppressed.

Was it really an assassination attempt, or just a suicide by cop? What does a 20-year old victim of bullying in rural Pennsylvania really know about Donald Trump? Enough to be angry enough to want to kill him? Or was it the MAGA crowd that the would-be assassin reacted to? The perpetrator had to know that he would die as a result of his action. Maybe, he wanted to do something that would be remembered before exiting. Apart from the fireman who died accidentally, this was pretty much a nothing-burger, amplified by the media's mechanical response to this kind of thing.